Films

The First Witness, known as THE FIRST, is a short documentary film narrated by Ho Van Tay, a member of the Vietnamese Journalists League, who was invited by Pol Pot and leng Sary to tour and record by photographs and video select Cambodian sites during the reign of the Khmer Rouge (1975-1979). After the Khmer Rouge collapsed in January 1979, Ho Van Tay had the opportunity to discover the infamous Phnom Penh prison S-21, where he and his comrade, Dinh Phong witnessed the aftermath of the horrors that were perpetrated there. The film also references Cambodia’s first archivist, Yin Nean, who at some personal risk embarked on an effort to locate and preserve the official archives of the Khmer Rouge regime for the benefit future generations of Cambodians and as a testimony for the world of the mass atrocities committed by the regime.

Youk Chhang

Director, Documentation Center of Cambodia

December 2006

Over a million Cambodians were evacuated from Phnom Penh and other cities when the Khmer Rouge took control of the country in 1975, and millions more lived through Democratic Kampuchea. They have first-hand knowledge of forced labor, Khmer Rouge propaganda, and the regime’s continual battles with its enemy, the Vietnamese. But Cambodians under the age of 35 – not to mention the rest of the world – have no such direct knowledge, and for many of them, “seeing is believing.”

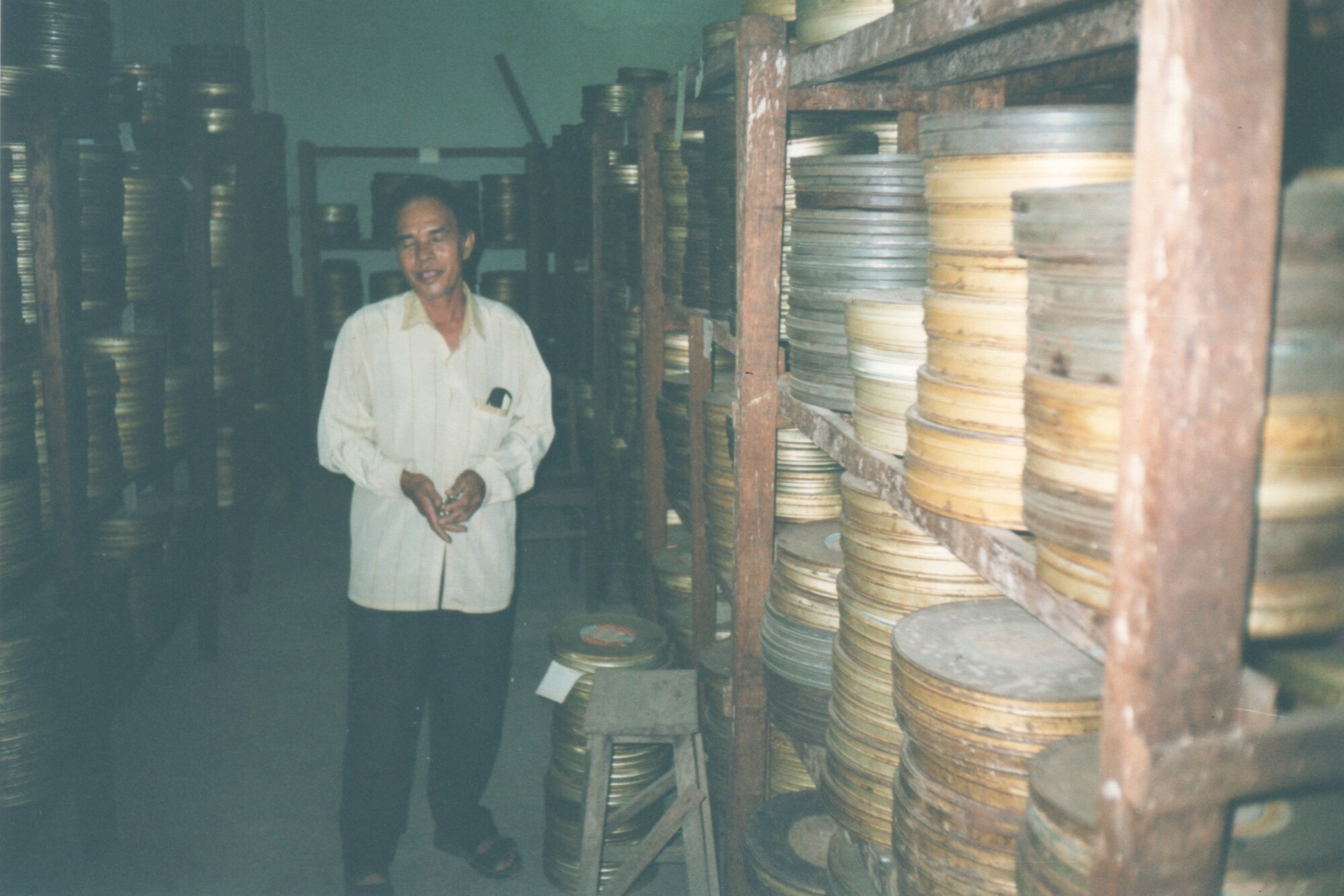

Convinced that they would stay in power forever, the Khmer Rouge filmed people working in the countryside, cadre and upper echelon meetings, and other events for posterity. For the purposes of propaganda, it also filmed reenactments of its battles with the Lon Nol Army and other military victories. After the regime was overthrown, these films were housed at the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts’ Cinema Department.

This cinematic record is of inestimable value to Cambodia, particularly in light of the trials of Khmer Rouge leaders, which are anticipated to begin in mid-2007. They include material that could help make cases against such senior Khmer Rouge leaders as Nuon Chea, Ieng Sary and Khieu Samphan. Equally important, these documents are crucial parts of the country’s modern history of genocide and could serve as educational tools for future generations of Cambodians. But they vanished in early 1998, and their whereabouts today is still uncertain.

The Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) and others have been following the films around the globe for nearly nine years, trying to retrieve them for the Cambodian people. But they have traveled under a cloud of secrecy, perhaps because many people stood to profit from them.

1998: The Films Leave Cambodia for France

In May 1998, DC-Cam asked the Cinema Department of the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts (MoCFA) for a list of the films it possessed that were made during Democratic Kampuchea. The Ministry sent a list to DC-Cam, stating that it held over 1,000 hours of film that comprised virtually all of the archival footage from the regime.

The MoCFA’s list contained 187 films: 36 from the Sihanouk period (1954-1970), 26 from the Khmer Republic (1970-1975), 101 from Democratic Kampuchea (1975-1979), and 24 films from the Peoples Republic of Kampuchea (1979-1992). The official list was signed by Bun Narith (department director) and Sok Song (archivist), and agreed to and approved by Minister Nouth Narang on March 4, 1998.

The 101 films from Democratic Kampuchea covered a variety of subjects. Some examples include:

- Scenes of everyday life during the regime: planting and harvesting, weaving, carrying earth, building dikes and canals, hill tribes

- Visits of foreign leaders sympathetic to the regime (e.g., Korea, Laos)

- Military: Khmer Rouge troops reenacting battles with Lon Nol soldiers and the Vietnamese military, the army’s entrance into Phnom Penh, and women combatants

- Political: a meeting of the Democratic Kampuchea congress at Olympic Stadium, the anniversary celebration of Cambodian communism, Pol Pot inspecting a dam.

There is also anecdotal evidence that some of the films contain images of King Norodom Sihanouk and Prime Minister Hun Sen.

Next, we wrote to Nouth Narang, then Minister of Culture and Fine Arts, asking to see the films. But by the time permission was granted, we found only an empty room at the Ministry. MoCFA employees told us that the films had been sent to France for “restoration.” They also told me informally that the films would “never be returned unless the Government pays money to get them back.”

1999-2002: The Films’ Location is Discovered, but the Secrecy Continues

In January 1999, acting on an anonymous tip, a Reuters reporter questioned Daniel Renouf, the chairman of System-TV in Boulogne (France’s sixth-largest television company), about the missing films. He confirmed that System-TV had the films and said it had restored all of them. This gave us hope that the films would soon be returned to Cambodia, especially when M. Renouf acknowledged that they belonged to the Cambodian Government.

Later, however, the company changed its story. First, it claimed to have only 40 hours of historical film from Cambodia, and only about 10 hours of them dealt with the Khmer Rouge period. M. Renouf also suggested that the films would “probably not provide evidence,” and that more important films could exist in Vietnam or Eastern Europe, where the original processing was done. Second, M. Renouf stated that his company would restore the reels within “four to five months.”

While M. Renouf also said that System-TV was restoring the films for free, over the next three years, the company again changed its position. System-TV publicly stated that Cambodians must buy the films if they wanted them returned. And at one point, M. Renouf told me in a private conversation that System-TV did not have the films at all.

It soon became a matter of public record that Nouth Narang had signed a one-page contract with M. Renouf that turned the films over to System-TV. But the contract did not specify how much the French company had paid for them; nor did it mention a date when they were to be returned to Cambodia.

We made repeated attempts to contact Minister Nouth, but our messages went unanswered. Although we also contacted various other officials of the Royal Cambodian Government, they generally denied responsibility for the films’ recovery or said they were “too busy” to deal with the matter.

Likewise, the French side did not seem inclined to be forthcoming about the films. Officials at the French Embassy refused to interfere because the films were held by private interests. And M. Renouf stated that the 1998 agreement prevented him from releasing the films until instructed to do so by the MoCFA, adding that he had received no official requests from them. “We are keeping them in safe condition here, keeping them in the proper condition. If the Government wants it back, all they have to do is ask,” he said.

In the interim, segments of the films began appearing in contemporary documentaries, leading DC-Cam to conclude that the restoration work had been somewhat completed. It also seemed that the French station was holding the films as a unique archive, and that the archive was likely for sale.

2006-2006: The Web of Deceit Continues

In mid-2002, the case was handed over to the Cambodian Council of Ministers’ AntiCorruption Unit. Som Sokun, director of the MoCFA’s Cinema Department, also went public, saying the government had asked that the film collection be returned. Mr. Som had gathered many of the films beginning in 1979, when Khmer Rouge documents were being thrown out and burned following the collapse of Democratic Kampuchea.

The issue again came before the public when a story entitled “Historic Film Archive Languishing in France” appeared in the April 25-May 8, 2003 edition of a local newspaper, the Phnom Penh Post. In it, Nouth Narang, who was by then a Member of Parliament, was quoted as saying he had seen the films in 1999 and had been shocked at their condition: half of them had already been stolen or destroyed, he said. Minister Nouth also denied selling the films, stating they had been sent to France only for the purposes of conserving them. “The press said I sold the films but it’s not true,” he said. “What I did was purely cultural.”

Sean Visoth, then head of the Anti-Corruption Unit, fueled the controversy when he was quoted as saying that Youk Chhang “doesn’t have enough evidence to substantiate the matter. I will look into this matter if the Ministry of Culture makes a request to the Council of Ministers. If there’s no complaint from the victim, then the police can’t do anything,” he said.

Edwige Laforět, a French film researcher, added another layer of mystery to the films’ whereabouts. She insisted they were hidden in the huge French archive, Pathé Library. She stated, “It seems true that the deal between System-TV and Pathé was first to restore them, then to come to a distribution agreement which would have been a big robbery.” The Phnom Penh Post investigated Pathé’s website, which did not show that it had any footage shot during Democratic Kampuchea. The library did not respond to the newspaper’s requests for information.

Daniel Renouf, who was also interviewed for the article, claimed that the films were still at System-TV, where they were being kept in professional storage. This time, however, he contradicted his earlier statements regarding the restoration; $65,000 was now needed for this task, he said. M. Renouf promised that as soon as he was able to get official funds, he would return them to the Ministry, whose head was then Princess Bopha Devi.

He also reiterated that if the Ministry of Fine Arts and Culture wanted the films back, all it had to do was ask. Posing a challenge to DC-Cam, he added, “If… Chhang wants to view the films, he should consult the director of MoCFA’s Cinema Department.”

DC-Cam countered by writing the editor of the Phnom Penh Post, quoting a letter it held from His Excellency Deputy Prime Minister Sok An:

“The Royal Government of Cambodia has agreed to authorize you to search for all types of documents about/related to the genocide in Cambodia and other countries through your NGO the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam).”

There was no further response from Mr. Renouf.

The next person to enter the fray was Cambodian filmmaker Rithy Panh, who lives in France. He also attempted to review the films, but was rebuffed by System-TV, which said he needed permission from the MoCFA. Others, such as the American television program 60 Minutes tried as well, but System-TV told them that they did not have the rights to screen the films.

A Private Company Tries to Track Down the Films

The situation languished until late March 2006, when a series of communications began between James Lindner of Media Matters (a New York-based firm specializing in archival audio and visual materials) and the National Archives of Cambodia. Mr. Lindner was working with the National Archives and had become intrigued by the matter of the missing films, so he decided to try and locate them. Mr. Lindner contacted the state-owned National Audio-Visual Institute (INA) in Paris, which said it would check on the status of the films. He took this as a positive indication that INA had some or all of the footage from Democratic Kampuchea.

Mr. Lindner then wrote to His Excellency Chea Sophorn, Secretary of State of the Council of Ministers, asking if he would write an informal letter to the INA requesting assistance from them in locating the films and returning copies to Cambodia. Although there was no response, in April, Mr. Lindner received an unofficial confirmation from INA that it was holding the films.

Later that month, Emmanuel Hoog of the INA wrote to Mr. Lindner, stating that his organization had concluded an agreement with the Cambodian Ministry of Culture. The agreement entrusted the restoration and preservation of the films to the INA. He also stated that the INA was going to restore the originals and send a copy to the Cambodian authorities. What was contained in that agreement is not publicly known.

Mr. Lindner replied to Mr. Hoog, copying Ms. Lim Ky of the National Archives and H.E. Chea Sophorn. He told Mr. Hoog that neither the National Archives nor the Council of Ministers had a copy of the agreement between the MoCFA and INA, and requested more information. He also asked Mr. Hoog to clarify the current status of the INA’s film restoration efforts and when they would be concluded. Last, Mr. Lindner asked that the INA provide the Archives with digital copies of the materials in the meantime so they would be able to know the contents of the films the INA was holding.

Mr. Hoog sent a curt reply in May that avoided answering nearly all of Mr. Lindner’s questions. It stated that his organization had been in contact only with the new Minister of Culture, Sisowath Panara Sereyvuth, who had signed the agreement. Perhaps sensing that he was walking through a political minefield, Mr. Hoog was firm: the National Archives must deal with Minister Sisowath on this matter.

For its part, the National Archives replied that it was “discussing” the preparation of a letter for Mr. Lindner with the Secretary General of SEAPAVAA (the South East Asia Pacific Audio-Visual Archive Association), Jamie Lean. Its representative also said that it was working with the SEAPAVAA Committee for Repatriation Project.

In May, the National Archives notified Mr. Lindner that the Secretary General of SEAPAVAA had replied to them informally. He stated that he was very happy about the recent developments to recover the films, and that he would talk to Minister Sisowath about them. He also promised to inform Mr. Lindner when he had sufficient information on the status of the films.

The National Archives also informed Mr. Lindner of a new twist in the case: a project of the French Embassy – the Hanuman Audiovisual Resource Center Cambodia – was working on the films with the MoCFA’s Cinema Department (but not with the National Archives). The Archives stressed that while the Hanuman Center could collect films, they could not legally keep them. They cited Cambodia’s Archives Law, which states that all Cambodian ministries must transfer their archives to the National Archives, and all non-government organizations working in Cambodia must give a copy of their projects to the National Archives.

Mr. Lindner then wrote to Hanuman, asking about its role. The NGO’s reply was vague: the organization was collecting digitized copies of all audio-visual archives that are relevant to Cambodian history, traditions, or culture. Noting that Hanuman has no legal mandate, the organization reaffirmed that it only intended to collect digitized copies of films, both in Cambodia and abroad.

Curious about the films from Democratic Kampuchea, Mr. Lindner wrote to Hanuman again, asking if they knew anything about the status of the footage in the INA’s custody, whether they knew what condition they were in, whether they had been restored, and when the National Archives could expect to receive a digitized copy. He asked several other questions, including whether Hanuman had seen a copy of the contract with the INA, and whether Hanuman would cooperate with the National Archives. He had not received a reply by November 2006 and it seemed that the trail was growing cold.

The Truth Remains to be Revealed

DC-Cam has information that points to the whereabouts of the missing films, although we have not been able to pinpoint their exact location. We know, for example, that Hanuman has changed its name and is now known as Bophana; it is headed by Rithy Panh. The organization’s website says that it is cooperating with the INA and Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, among others. Its website also notes that the MoCFA has entrusted the Center for Audiovisual Resources (Bophana’s parent organization) with a large collection of documents to be restored and digitized. And the Ministry has also made a building in its compound available to the Center.

Does Bophana have the missing films? In response to DC-Cam’s questions, Rithy Panh claims that it does not, saying only that the restoration is still incomplete. And while Bophana’s while website says that it has over 900 documents from Cambodia, its search engine is not yet operating, making it impossible for the public to know what the NGO does have in its archives.

If Bophana has the films, when will it make them available to the Cambodian public? Will they be restored in time to serve as potential evidence in the Khmer Rouge tribunal? And will Bophana comply with the law and turn copies over to the National Archives?

In the end, it doesn’t really matter where the films have been, what money changed hands, and who was telling the truth. What matters is that the films are returned to Cambodia, their rightful owner.

The Missing Film.

English

Contact

ROS SAMPEOU

DIRECTOR OF ARCHIVES THE QUEEN MOTHER LIBRARY

t: +855 (0) 12 882 505

e: truthsampeou.r@18.139.249.29